Russian political figure, publicist Vasily Vitalievich Shulgin was born on January 13 (January 1, old style) 1878 in Kyiv in the family of the historian Vitaly Shulgin. His father died the year his son was born, the boy was raised by his stepfather, scientist-economist Dmitry Pikhno, editor of the monarchist newspaper "Kievlyanin" (replaced Vitaly Shulgin in this position), later a member of the State Council.

In 1900, Vasily Shulgin graduated from the Faculty of Law of Kyiv University, and studied for another year at the Kiev Polytechnic Institute.

He was elected zemstvo councilor, an honorary justice of the peace, and became the leading journalist of Kievlyanin.

MP II, III and IV State Duma from the Volyn province. First elected in 1907. Initially he was a member of the right-wing faction. He participated in the activities of monarchist organizations: he was a full member of the Russian Assembly (1911-1913) and was a member of its council; took part in the activities of the Main Chamber of the Russian People's Union named after. Michael the Archangel, was a member of the commission for compiling the “Book of Russian Sorrow” and the “Chronicle of the Troubled Pogroms of 1905-1907”.

After the outbreak of World War I, Shulgin volunteered to go to the front. With the rank of ensign of the 166th Rivne Infantry Regiment of the Southwestern Front, he participated in battles. He was wounded, and after being wounded he led the Zemstvo forward dressing and nutritional detachment.

In August 1915, Shulgin left the nationalist faction in the State Duma and formed the Progressive Group of Nationalists. At the same time, he became part of the leadership of the Progressive Bloc, in which he saw the union of the “conservative and liberal parts of society,” becoming closer to former political opponents.

In March (February old style) 1917, Shulgin was elected to the Provisional Committee of the State Duma. On March 15 (March 2, old style), he, along with Alexander Guchkov, was sent to Pskov for negotiations with the emperor and was present at the signing of the manifesto of abdication in favor of Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich, which he later wrote about in detail in his book “Days.” The next day - March 16 (March 3, old style) he was present at the renunciation of Mikhail Alexandrovich from the throne and participated in the preparation and editing of the act of abdication.

According to the conclusion of the Prosecutor General's Office Russian Federation on November 12, 2001, he was rehabilitated.

In 2008, in Vladimir, at house No. 1 on Feigina Street, where Shulgin lived from 1960 to 1976, a memorial plaque was installed.

The material was prepared based on information from open sources

During the filming of the film "Before the Judgment of History" (1964). Monarchist V.V. Shulgin in the Kremlin Palace of Congresses

One of the varieties of monarchists who lived in the USSR (along with dissident monarchists) were monarchists who acted within the framework of Soviet legality. The most striking example of such a figure is Vasily Vitalievich Shulgin (1878-1976). True, before becoming “the most important Soviet monarchist,” he had to serve his time in Vladimir prison. And even then he was lucky in the sense that in 1947, when he was tried, the death penalty in the USSR has already been abolished.

But in September 1956, Shulgin was released. He by no means renounced his monarchist views, and he himself later wrote: “Had he been pardoned and repented, Shulgin would not have been worth a penny and could only have evoked contemptuous regret.” But he tried to adapt his old beliefs to the new reality and, moreover, express them openly. And the most amazing thing is that he succeeded... With the skill and talent of an experienced parliamentary speaker, Shulgin persistently pushed the ideas of monarchism and Stolypinism into legal Soviet politics and journalism. He masterfully put them into a very neat, censorship-acceptable form. And he did - both in his book, “Letters to Russian Emigrants,” published in the 60s, and in the documentary film “Before the Judgment of History,” which was made about him at the same time. And in other works, including memoirs that were published after his death, in 1979, by the APN publishing house. Shulgin met with public figures related to him: for example, none other than Alexander Solzhenitsyn came to him in Vladimir. Shulgin's articles appeared in Pravda, he spoke on the radio. And, finally, as the pinnacle of everything, the former ideologist of the White Guard and the author of the slogan “Fascists of all countries, unite!” was invited to the XXII Congress of the CPSU in 1961 and took part in it as a guest.

During the filming of "Before the Judgment of History." In the Tauride Palace (Leningrad), Shulgin points to the place he occupied in the meeting room of the former State Duma

How did he manage to do this? I once wrote that prohibiting the expression of any views only leads to them being neatly masked with a layer of cotton candy. A more stringent prohibition leads to being wrapped in two, three, ten layers of cotton candy... But the inner grain does not disappear anywhere, it just becomes more difficult to recognize it under the honey shell and object to it. Shulgin mastered this art to the fullest.

Soviet director and communist Friedrich Ermler recalled his meeting with Shulgin at Lenfilm: “If I had met him in 1924, I would have done everything to ensure that my conclusion ended with the word “shoot.” And suddenly I saw the Apostle Peter, blind, with a cane. An old man appeared in front of me, looked at me for a long time, and then said: “You are very pale. You, my dear, need to be taken care of. I am a bison, I will stand...”.” In other words, instead of a fierce class enemy, which Shulgin undoubtedly was (by the way, the word “bison” before the revolution meant an ardent monarchist Black Hundred, in this sense it was used by Lenin), his Soviet opponents were amazed to discover almost a saint. He was reminded of his former, by no means holy, words and feelings (published, by the way, in the USSR back in the 20s along with Shulgin’s book “Days”); for example, at the sight of a revolutionary street crowd in February 1917:

“Soldiers, workers, students, intellectuals, just people... The endless, inexhaustible stream of the human water supply threw more and more new faces into the Duma... But no matter how many of them there were, they all had the same face: vile-animal-stupid or vile -devilishly evil... God, how disgusting it was! So disgusting that, gritting my teeth, I felt in myself only melancholy, powerless and therefore even more evil fury... Machine guns - that’s what I wanted. For I felt, that only the language of machine guns is accessible to the street crowd and that only he, lead, can drive back into his den the terrible beast that has broken free... Alas - this beast was... His Majesty the Russian people... Ah, machine guns here, machine guns! .."

Books by V.V. Shulgin, published in the USSR in the 20s

Vasily Vitalievich responded evasively and eloquently to reminders: it was the case, I wrote, I don’t renounce. But one cannot deny the passage of time... Can today’s Shulgin, with a big white beard, repeat what that Shulgin with a black mustache said?..

The film “Before the Judgment of History,” which became Ermler’s “swan song,” was difficult to film; filming lasted from 1962 to 1965. The reason was that the obstinate monarchist “showed character” and did not agree to utter a single word on camera with which he himself did not agree. According to KGB General Philip Bobkov, who supervised the creation of the film from the department and closely communicated with all creative group, “Shulgin looked great on screen and, importantly, remained himself all the time. He did not play along with his interlocutor. He was a man who resigned himself to circumstances, but was not broken and did not give up his convictions. Shulgin's venerable age did not affect his work of thought or temperament, and did not diminish his sarcasm. His young opponent, whom Shulgin caustically and angrily ridiculed, looked very pale next to him.” The Lenfilmov large-circulation newspaper “Kadr” published the article “Meeting with the Enemy.” In it, director, People's Artist of the USSR and Ermler's friend Alexander Ivanov wrote: “The appearance on the screen of a seasoned enemy of Soviet power is impressive. The inner aristocracy of this monarchist is so convincing that you listen not only to what he says, but watch with tension how he speaks... Now he is so decent, at times pitiful and even seemingly cute. But this is a terrible man. These people were followed by hundreds of thousands of people who laid down their lives for their ideas.”

As a result, the film was shown on wide screens in Moscow and Leningrad cinemas for only three days: despite the great interest of the audience, it was withdrawn from distribution ahead of schedule, and was then rarely shown.

And Shulgin was also dissatisfied with his book “Letters to Russian Emigrants” for its lack of radicalism, and in 1970 he wrote about it like this: “I don’t like this book. There are no lies here, but there are mistakes on my part, an unsuccessful deception on the part of some people. Therefore, the "Letters" did not achieve their goal. The emigrants did not believe both what was incorrect and what was stated accurately. It is a pity."

Shulgin's conversation with the old Bolshevik Petrov

The culmination of the film “Before the Judgment of History” was Shulgin’s meeting with the legendary revolutionary, member of the CPSU since 1896, Fyodor Nikolaevich Petrov (1876-1973). A meeting between an old Bolshevik and an old monarchist. On the screen, Vasily Vitalievich literally flooded his opponent with an oil of praise and compliments, thereby completely disarming him. At the end of the conversation, a softened Petrov agreed to shake hands with Shulgin on camera. And behind the scenes, Vasily Vitalievich spoke about his opponent, as befits a class enemy, sarcastically and contemptuously: “In the film “Before the Judgment of History,” I had to come up with dialogues with my opponent, the Bolshevik Petrov, who turned out to be very stupid.”

At the end of the conversation, Petrov agreed to shake Shulgin’s hand

By the way, Shulgin’s presence in political life Public opinion perceived the USSR rather disapprovingly. This can be judged, in particular, by the well-known joke “What did Nikita Khrushchev do and what did he not have time to do?” “I managed to invite the monarchist Shulgin as a guest to the XXII Party Congress. I did not have time to posthumously award Nicholas II and Grigory Rasputin with the order October revolution for the creation of a revolutionary situation in Russia." That is, the "political resurrection" of Shulgin in the 60s, and especially the invitation of the monarchist to the Congress of the Communist Party, was widely regarded as a manifestation of Khrushchev's "voluntarism" (to put it simply, absurd tyranny). However, the film "Before the court of history" was released when Khrushchev was no longer in the Kremlin, and Shulgin's memoirs "The Years" appeared in print in the late 70s.

Shulgin shows his "patriotism"

Books by V.V. Shulgin, published in the USSR in the 60s and 70s

Memorial plaque installed on January 13, 2008, on the 130th anniversary of Shulgin’s birth at house No. 1 on Feigina Street in Vladimir

Poster for the film "Before the Judgment of History":

Film "Before the Judgment of History"

Shulgin Vasily Vitalievich - (January 13, 1878 - February 15, 1976) - Russian nationalist and publicist. Deputy of the second, third and fourth State Duma, monarchist and participant in the White movement.

Shulgin was born in Kyiv in the family of historian Vitaly Shulgin. Vasily’s father died a month before his birth, and the boy was raised by his stepfather, scientist-economist Dmitry Pikhno, editor of the monarchist newspaper “Kievlyanin” (replaced V. Ya. Shulgin in this position), later a member of the State Council. Shulgin studied law at Kiev University. He developed a negative attitude towards the revolution while still at university, when he constantly witnessed riots organized by revolutionary-minded students. Shulgin's stepfather got him a job at his newspaper. In his publications, Shulgin promoted anti-Semitism. For tactical reasons, Shulgin criticized the Beilis case, since it was obvious that this odious process played into the hands only of opponents of the monarchy. This served as a reason for criticism of Shulgin by some radical nationalists, in particular, M. O. Menshikov called him a “Jewish Janissary” in his article “Little Zola”

In 1907, Shulgin became a member of the State Duma and leader of the nationalist faction in the IV Duma. He championed far-right views and supported the Stolypin government, including the introduction of courts-martial and other controversial reforms. With the outbreak of World War I, Shulgin went to the front, but in 1915 he was wounded and returned. On February 27, 1917, the Council of Elders of the Duma V.V. Shulgin was elected to the Temporary Committee of the State Duma, which assumed the functions of the government. The Provisional Committee decided that Emperor Nicholas II should immediately abdicate the throne in favor of his son Alexei under the regency of his brother Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich.

On March 2, the Provisional Committee sent V.V. to the Tsar in Pskov for negotiations. Shulgin and A.I. Guchkova. But Nicholas II signed the Act of Abdication in favor of his brother, Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich. March 03 V.V. Shulgin took part in negotiations with Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich, as a result of which he refused to accept the throne until the decision of the Constituent Assembly. April 26, 1917 V.V. Shulgin admitted: “I won’t say that the entire Duma entirely wanted the revolution; all this would be untrue... But, even without wanting it, we created a revolution.”

V.V. Shulgin strongly supported the Provisional Government, but, seeing its inability to restore order in the country, at the beginning of October 1917 he moved to Kyiv. There he headed the Russian National Union.

After the October Revolution V.V. Shulgin created the underground organization "Azbuka" in Kyiv with the aim of fighting Bolshevism. In November-December 1917 he went to the Don to Novocherkassk and participated in the creation of the White Volunteer Army. From the end of 1918 he edited the newspaper "Russia", then " Great Russia", praising the monarchical and nationalist principles and the purity of the "white idea." When hope for the anti-Bolshevik forces to come to power was lost, Shulgin first moved to Kyiv, where he took part in the activities of the White Guard organizations (Azbuka), and later emigrated to Yugoslavia.

In 1925-26 he secretly visited Soviet Union, describing his impressions of the NEP in the book Three Capitals. In exile, Shulgin maintained contacts with other figures of the White movement until 1937, when he finally stopped political activities. In 1925-1926. arrived in Russia illegally, visited Kyiv, Moscow, Leningrad. He described his visit to the USSR in the book “Three Capitals” and summed up his impressions with the words: “When I went there, I didn’t have a homeland. Now I have one.” Since the 30s. lived in Yugoslavia.

In 1937 he retired from political activity. When Soviet troops entered the territory of Yugoslavia in 1944, V.V. Shulgin was arrested and transported to Moscow. For “hostile communism and anti-Soviet activities” he was sentenced to 25 years in prison. He served his time in Vladimir prison, working on his memoirs. After the death of I.V. Stalin, during the period of a broad amnesty for political prisoners in 1956, was released and settled in Vladimir.

In the 1960s called on emigration to refuse hostility to the USSR. In 1965, he starred in the documentary film “Before the Judgment of History”: V.V. Shulgin, sitting in the Catherine Hall of the Tauride Palace, where the State Duma met, answered the historian’s questions.

After the summer break, we continue under the heading “Historical Calendar” . The project, which we called “Gravediggers of the Russian Kingdom,” is dedicated to those responsible for the collapse of the autocratic monarchy in Russia - professional revolutionaries, confrontational aristocrats, liberal politicians; generals, officers and soldiers who have forgotten about their duty, as well as other active figures of the so-called. “liberation movement”, voluntarily or unwittingly, contributed to the triumph of the revolution - first the February, and then the October. The column continues with an essay dedicated to a prominent Russian politician, deputyII‒IV State Duma, one of the leaders of Russian nationalism V.V. Shulgin, whose lot it fell to accept the abdication of Emperor NicholasII.

Born on January 1, 1878 in the family of a hereditary nobleman, professor of general history at the Kyiv University of St. Vladimir V.Ya. Shulgin (1822-1878), who published the patriotic newspaper “Kievlyanin” from 1864. However, in the year of Vasily’s birth, his father died and the future politician was raised by his stepfather, professor-economist D.I. Pikhno, who had a great influence on the formation of Shulgin’s political views.

After graduating from the 2nd Kyiv Gymnasium (1895) and the Law Faculty of Kiev University (1900), Vasily Shulgin studied for a year at the Kiev Polytechnic Institute, after which in 1902 he served military service in the 3rd Engineer Brigade, retiring with the rank of field ensign engineering troops. Returning after completing his military service to the Volyn province, Shulgin took up agriculture, but the war with Japan that soon began caused an upsurge of patriotic feelings in him, and the reserve officer volunteered to go to the theater of military operations. However, this war, unsuccessful for Russia, ended before Shulgin managed to reach the front. The young officer was sent to Kyiv, where he had to take part in restoring order disrupted by the revolution. Shulgin later expressed his attitude towards the revolution of 1905, which he then referred to only as “Its Trash”. in the following words: “We knew that a revolution was underway - merciless, cruel, which was already spewing blasphemy against everything holy and dear, which would trample the Motherland into the mud, if now, without waiting a minute longer, we did not give it... “in the face””. After retiring, V.V. Shulgin settled on his estate, where he continued farming and social work (he was a zemstvo councilor), and also became interested in journalism, quickly becoming the leading journalist of Kievlyanin.

Shulgin appeared on the political scene already at the end of the revolution - in 1907. The impetus for his political activity was the desire of the Poles to appoint only their own candidates to the State Duma from the Kyiv, Podolsk and Volyn provinces. Not wanting to allow such an outcome of the election campaign, Shulgin took an active part in the elections to the Second Duma, trying in every possible way to stir up local residents who were indifferent to politics. The campaigning brought Vasily Vitalievich popularity, and he himself turned out to be one of the candidates for deputy, soon becoming a deputy. In the “Duma of Popular Ignorance” Shulgin joined the few rightists: , P.A. Krushevan, Count V.A. Bobrinsky, Bishop Platon (Rozhdestvensky) and others, soon becoming one of the leaders of the conservative wing of the “Russian parliament”.

As is known, the activities of the Second Duma took place during a period when revolutionary terror was still in full swing, and introduced by P.A. Stolypin's military courts severely punished revolutionaries. The Duma, composed primarily of representatives of the radical left and liberal parties, seethed with anger at the government's brutal suppression of the revolution. Under these conditions, Shulgin demanded a public condemnation of revolutionary terror by the liberal-left majority of the Duma, but it avoided condemning the revolutionary terrorists. In the midst of attacks on the brutality of the government, Shulgin asked the Duma majority a question: “I, gentlemen, ask you to answer: can you honestly and honestly say to me: “Does any of you, gentlemen, have a bomb in your pocket?”. And although in the hall sat representatives of the Socialist Revolutionaries, who openly approved of the terror of their militants, as well as liberals who were in no hurry to condemn the revolutionary terror of the left, which was beneficial to them, they were “offended” by Shulgin. Amid leftist cries of “vulgar!” he was removed from the boardroom and became "notorious" as a "reactionary".

Soon becoming famous as one of the best right-wing speakers, Shulgin always stood out for his emphatically correct manners, speaking slowly, restrainedly, sincerely, but almost always ironically and poisonously, for which he even received a kind of panegyric from Purishkevich: “Your voice is quiet, and your appearance is timid, / But the devil is in you, Shulgin, / You are the Bickford cord of those boxes, / Where the pyroxylin is placed!”. Soviet author and contemporary Shulgin D.O. Zaslavsky left what appears to be very accurate evidence of how the right-wing politician was perceived by his political opponents: “There was so much subtle poison, so much evil irony in his polite words, in his correct smile, that one immediately felt an irreconcilable, mortal enemy of the revolution, democracy, even just liberalism... He was hated more than Purishkevich, more than Krushevan, Zamyslovsky, Krupensky and other Duma Black Hundreds... Shulgin was always impeccably polite. But his calm, well-calculated attacks brought the State Duma to white heat.”.

Vasily Shulgin was a staunch supporter of Stolypin and his reforms, which he supported with all his might from the Duma pulpit and from the pages of “Kievlyanin”. In the Third Duma, he joined the Council of the most conservative parliamentary group - the right-wing faction. During this period, Shulgin was a like-minded person of such prominent leaders of the Black Hundred movement as V.M. Purishkevich and N.E. Markov. He was the honorary chairman of one of the Volyn departments of the Union of the Russian People, was a full member of the Russian Assembly, even holding the position of fellow chairman of the Council of this oldest monarchist organization until the end of January 1911. Working closely with Purishkevich, Shulgin took part in meetings of the Main Chamber of the Russian People's Union named after. Michael the Archangel, was a member of the commission for compiling the “Book of Russian Sorrow” and the “Chronicle of the Troubled Pogroms of 1905-1907”. In 1909-1910 he has repeatedly published articles on national question in the RNSMA magazine “Straight Path”. However, after the unification of the moderate right with Russian nationalists, Shulgin found himself in the ranks of the Main Council of the conservative-liberal All-Russian National Union (VNS) and left all Black Hundred organizations, setting a course for rapprochement with the moderate opposition.

Despite anti-Semitism, which, by Shulgin’s own admission, was inherent in him since his student years, the politician had a special position on the Jewish issue: he advocated granting equal rights to Jews, and in 1913 he went against the position of the leadership of the Supreme Soviet, publicly condemning the initiators of the “Beilis Affair” , protesting from the pages of “Kievlyanin” against “accusing an entire religion of one of the most shameful superstitions.” (Mendel Beilis was accused of the ritual murder of 12-year-old Andrei Yushchinsky). This speech almost cost Shulgin a 3-month prison sentence “for disseminating deliberately false information about senior officials in the press,” but the Emperor stood up for him, deciding to “consider the matter not to have happened.” However, the rightists did not forgive their former ally for this trick, accusing him of corruption and betrayal of a just cause.

In 1914, when the First World War broke out World War, V.V. Shulgin changed his deputy frock coat to an officer's uniform, volunteering to go to the front. As an ensign of the 166th Rivne Infantry Regiment, he took part in battles on the Southwestern Front and was wounded during one of the attacks. Having recovered from his wound, Shulgin served for some time as the head of the zemstvo advanced dressing and nutritional detachment, but in the second half of 1915 he again returned to his deputy duties. With the formation of the liberal Progressive Bloc in opposition to the government, Shulgin found himself among its supporters and became one of the initiators of the split in the Duma faction of nationalists, becoming one of the leaders of the “progressive nationalists” who joined the bloc. Shulgin explained his action with a patriotic feeling, believing that “The interest of the present moment prevails over the precepts of the ancestors.” While in the leadership of the Progressive Bloc, Vasily Vitalievich became close to M.V. Rodzianko, and other liberal figures. Shulgin’s views at that time are perfectly characterized by the words from his letter to his wife: “How nice it would be if the stupid rightists were as smart as the Cadets and tried to restore their birthright by working for the war... But they cannot understand this and are spoiling the common cause.”.

But, despite the fact that de facto Shulgin found himself in the camp of the enemies of the autocracy, he still quite sincerely continued to consider himself a monarchist, apparently having forgotten his own conclusions about the revolution of 1905-1907, when, in his own words, “liberal reforms only incited revolutionary elements and pushed them to take active action”. In 1915, from the Duma rostrum, Shulgin protested against the arrest and criminal conviction of Bolshevik deputies, considering this act illegal and a “major state mistake”; in October 1916 he called for the “great goal of the war” “to achieve a complete renewal of power, without which achieving victory is unthinkable and urgent reforms are impossible”, and on November 3, 1916, he gave a speech in the Duma in which he criticized the government, practically standing in solidarity with the thunder. In this regard, the leader of the Union of Russian People N.E. Markov noted in exile, not without reason: “The “right” Shulgin and Purishkevich turned out to be much more harmful than Miliukov himself. After all, only they, and the “patriot” Guchkov, and not Kerensky and Co., were trusted by all these generals who made the revolution a success.”.

Shulgin not only accepted the February Revolution, but also became an active participant in it. On February 27, he was elected by the Duma Council of Elders to the Temporary Committee of the State Duma (VKGD), and then for a day became commissioner of the Petrograd Telegraph Agency. Shulgin also took part in compiling the list of ministers of the Provisional Government, as well as the goals of its program. When the VKGD advocated the immediate abdication of Emperor Nicholas II from the throne, this task, as is known, was entrusted by the revolutionary authorities to Shulgin and the leader of the Octobrists, who completed it on March 2, 1917. Without ceasing to consider himself a monarchist and perceiving what happened as a tragedy, Shulgin reassured himself that the Emperor’s abdication provided a chance to save the monarchy and the dynasty. “The culminating moment of revealing one’s personality was the participation of V.V. Shulgin in the tragic moment of the abdication of Emperor Nicholas II, ‒ wrote cadet E.A. Efimovsky . ‒ I once asked Vasily V[italevich]: how could this happen. He burst into tears and said: we never wanted this; but, if this was to happen, the monarchists should have been near the Emperor, and not left him to explain himself to his enemies.”. Shulgin would later explain his participation in the renunciation in these words: during the days of the revolution “Everyone was convinced that the transfer of power would improve the situation”. Emphasizing his respect for the personality of the Emperor, Shulgin criticized him for “lack of will,” emphasizing that “Nobody listened to Nikolai Alexandrovich at all”. Justifying his action, Shulgin gave the following arguments in his defense: “The issue of renunciation was a foregone conclusion. It would have happened regardless of whether Shulgin was present or not. He considered that at least one monarchist should be present... Shulgin feared that the Emperor might be killed. And he went to the Dno station with the goal of “creating a shield” so that the murder would not happen.”. Vasily Vitalievich had a chance to become a participant in negotiations with Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich, as a result of which he refused to take the throne until the decision of the Constituent Assembly, in connection with which he later stated that he “ a convinced monarchist... had, by some evil irony of fate, been present at the abdication of two Emperors.”. In exile, responding to numerous reproaches from the monarchist camp and to accusations of “betrayal,” Shulgin rather self-confidently declared that he had fulfilled the last duty of a loyal subject to Nicholas II: “by renunciation, performed almost like a sacrament, [managed] to erase in human memory everything that led to this act, leaving only greatness last minute» . Even almost half a century after the events described, Shulgin continued to claim that although he “accepted abdication from the hands of the Emperor, but did it in a form that I dare to call gentlemanly”.

But then, immediately after the coup, Shulgin excitedly informed the readers of his newspaper “Kievlyanin”: “A revolution unheard of in the history of mankind took place - something fabulous, incredible, impossible. Within twenty-four hours, two Sovereigns abandoned the throne. The Romanov dynasty, having stood at the head of the Russian State for three hundred years, relinquished power, and, by a fatal coincidence, the first and last Tsar of this family bore the same name. There is something deeply mystical about this strange coincidence. Three hundred years ago, Michael, the first Russian Tsar from the House of Romanov, ascended the throne when, torn apart by terrible turmoil, Russia was all on fire with one common desire: “We need a Tsar!” Michael, the last Tsar, three hundred years later had to hear how the agitated masses of the people raised a menacing cry to him: “We don’t want a Tsar!” The revolution, as Shulgin wrote in those days, led to the fact that people “who love it” finally established themselves in power in Russia.

Shulgin answered about his political views during the revolutionary days as follows: “People often ask me: “Are you a monarchist or a republican?” I answer: “I am for the winners.”. Developing this idea, he explained that victory over Germany would lead to the establishment of a republic in Russia, “ and the monarchy can only be reborn after the horrors of defeat.”. "Under such conditions, - summarized V.V. Shulgin , - it turns out a strange combination when the most sincere monarchists, by all inclinations and sympathies, have to pray to God that we have a republic". “If this republican government saves Russia, I will become a republican”“,” he added.

However, despite the fact that Shulgin became one of the main heroes of February, disappointment in the revolution came to him quite quickly. Already at the beginning of April 1917, he wrote with bitterness: “ There is no need to create unnecessary illusions for yourself. There will be no freedom, no real freedom. It will come only when human souls are imbued with respect for other people's rights and other people's beliefs. But it won't be so soon. This will happen when the souls of democrats, strange as it may sound, become aristocratic.” Speaking in August 1917 at the State Conference in Moscow, Shulgin demanded “unlimited power,” the preservation of the death penalty, the prohibition of elected committees in the army, and the prevention of autonomy for Ukraine. And already on August 30, he was arrested during his next visit to Kyiv by the Committee for the Protection of the Revolution, as the editor of “Kievlyanin”, but was soon released. Shulgin later expressed his attitude towards the February events with the following words: “Machine guns - that’s what I wanted. For I felt that only the language of machine guns was accessible to the street crowd and that only he, the lead, could drive back into his lair the terrible beast that had broken free... Alas - this beast was... His Majesty the Russian people... What we were so afraid that we wanted to avoid it at all costs, it was already a fact. The revolution has begun". But at the same time, the politician admitted his guilt in the disaster: “I won’t say that the entire Duma entirely wanted the revolution; this would not be true... But even without wanting it, we created a revolution... We cannot renounce this revolution, we connected with it, we became welded together with it and bear moral responsibility for this.”.

After the Bolsheviks came to power, Shulgin moved to Kyiv, where he headed the Russian National Union. Without recognizing Soviet power, the politician began the fight against her, heading the illegal secret organization “ABC”, which was engaged in political intelligence and recruiting officers into the White Army. Considering Bolshevism a national catastrophe, Shulgin spoke of it as follows: “This is nothing more than a grandiose and extremely subtle German provocation, carried out with the help of a Russian-Jewish gang that fooled several thousand Russian soldiers and workers.”. In one of his private letters, Vasily Vitalievich wrote about the outbreak of the Civil War: “ Obviously we didn't like the fact that we weren't in the Middle Ages. We have been making a revolution for a hundred years... Now we have achieved it: the Middle Ages reign... Now families are cut down to the stump... and brother is responsible for brother.”.

On the pages of the Kievlyanin, which continued to appear, Shulgin fought against parliamentarism, Ukrainian nationalism and separatism. The politician took an active part in the formation of the Volunteer Army, categorically opposed any agreement with the Germans, and was outraged by the Brest Peace Treaty concluded by the Bolsheviks. In August 1918, Shulgin came to General A.I. Denikin, where he developed the “Regulations on the Special Meeting under the Supreme Leader of the Volunteer Army” and compiled a list of the Meeting. He published the newspaper “Russia” (then “Great Russia”), in which he praised monarchical and nationalist principles, advocated the purity of the “White Idea,” and collaborated with Denikin’s Information Agency (Osvag). At this time, Shulgin again revised his views. Shulgin’s brochure “The Monarchists” (1918) is very indicative in this regard, in which he was forced to state that after what happened to the country in 1917‒1918, “No one will dare anymore, except perhaps the most stupid, to talk about Stürmer, Rasputin, etc. Rasputin finally faded in comparison to Leiba Trotsky, and Sturmer was a patriot and statesman compared to Lenin, Grushevsky, Skoropadsky and the rest of the company.”. And that “old regime,” which seemed unbearable to Shulgin a year ago, now, after all the horrors of the revolution and civil war, “It seems almost heavenly bliss”. Defending the monarchical principle, in one of his newspaper articles Shulgin noted that “only monarchists in Russia know how to die for their Motherland”. But, advocating the restoration of the monarchy, Shulgin saw it no longer autocratic, but constitutional. However, the white generals did not dare to accept the monarchical idea even in the constitutional version.

After the end of the Civil War, the time of emigrant wanderings began for Shulgin - Turkey, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Poland, France. In the mid-1920s, he became the victim of a skillful provocation by Soviet intelligence, which went down in history as Operation Trust. In the fall of 1925, the emigre politician illegally crossed the Soviet border, making what he thought was a “secret” trip to the USSR, during which he visited Kiev, Moscow and Leningrad, accompanied by Trest agents, about which he later wrote the book “Three Capitals.” After the disclosure of this OGPU operation, which received wide publicity abroad, Shulgin’s credibility among emigrants was undermined, and from the second half of the 1930s he withdrew from active political activity.

On the eve of World War II, Shulgin lived in Sremski Karlovci (Yugoslavia), devoting himself to literary activity. In Hitler's invasion of the USSR, he saw a threat to the security of historical Russia and decided not to support the Nazis, but not to fight them either. This decision saved his life. When, after his arrest by Smersh in 1945, Shulgin was tried for thirty years (1907-1937) of anti-communist activity, the USSR MGB, taking into account the politician’s non-involvement in cooperation with the Germans, sentenced him to imprisonment for 25 years. After being in prison from 1947 to 1956, Shulgin was released early and settled in Vladimir. He had the opportunity not only to become the main character in the Soviet documentary-journalistic film “Before the Judgment of History” (1965), but also to participate as a guest at the XXII Congress of the CPSU. Taking, in essence, the position of National Bolshevism (already in emigration, the politician noted that under the shell of Soviet power processes were taking place “that have nothing in common... with Bolshevism”, that the Bolsheviks “restored the Russian army” and raised “the banner of United Russia” , that soon the country will be led by a “Bolshevik in energy and a nationalist in convictions,” and that the “former decadent intelligentsia” will be replaced by a “healthy, strong class of creators of material culture,” capable of fighting off the next “Drang nach Osten”), Shulgin characterized his attitude towards Soviet power: “My opinion, formed over forty years of observation and reflection, boils down to the fact that for the destinies of all mankind it is not only important, but simply necessary, that the communist experience, which has gone so far, should be unhinderedly completed... (...) The great suffering of the Russian people obliges us to do this. To survive everything that has been experienced and not achieve the goal? So all the sacrifices are in vain? No! The experience has gone too far... I cannot lie and say that I welcome the “Lenin Experience”. If it were up to me, I would prefer that this experiment be carried out anywhere, but not in my homeland. However, if it has been started and has gone so far, then it is absolutely necessary that this “Lenin Experience” be completed. And it may not be finished if we are too proud.”

The long 98-year life of Vasily Shulgin, covering the period from the reign of Emperor Alexander II to the reign of L.I. Brezhnev, ended on February 15, 1976 in Vladimir, on the feast of the Presentation of the Lord. They buried him in the cemetery church next to the Vladimir prison, where he spent 12 years.

At the end of his days, V.V. Shulgin became increasingly sensitive to his participation in the revolution and involvement in tragic fate Royal family. “My life will be connected with the Tsar and the Queen until last days mine, although they are somewhere in another world, and I continue to live - in this one. And this connection does not decrease over time. On the contrary, it is growing every year. And now, in 1966, this connectedness seemed to have reached its limit,‒ noted Shulgin . ‒ Every person in former Russia, if he thinks about the last Russian Tsar Nicholas II, he will certainly remember me, Shulgin. And back. If anyone gets to know me, then inevitably the shadow of the monarch who handed me the abdication of the throne 50 years ago will appear in his mind.”. Considering that “both the Sovereign and the loyal subject, who dared to ask for abdication, were victims of circumstances, inexorable and inevitable”, Shulgin at the same time wrote: “Yes, I accepted renunciation so that the Tsar would not be killed like Paul I, Peter III, Alexander II... But Nicholas II was still killed! And that is why I am condemned: I failed to save the Tsar, the Queen, their children and relatives. Failed! It’s as if I’m wrapped in a scroll of barbed wire that hurts me every time I touch it.”. Therefore, Shulgin bequeathed, “We must also pray for us, purely sinful, powerless, weak-willed and hopeless confused people. The fact that we are entangled in a web woven from the tragic contradictions of our century can be not an excuse, but only a mitigation of our guilt.”...

Prepared Andrey Ivanov, Doctor of Historical Sciences

In the early seventies, strange rumors circulated around Vladimir: supposedly, there lived in the city a monarchist who king Nicholas II He accepted the abdication, and shook hands with all the White Guard generals.

Such conversations seemed sheer madness: what kind of monarchist is there half a century after the October Revolution, after the country noisily celebrated the centenary of his birth? Lenin?!

The most amazing thing is that it was the pure truth. In the midst of Russian antiquities and Soviet buildings, not just a witness, but a major figure from the times of the revolution and the Civil War lived out his life. Moreover, this figure sacrificed her entire life on the altar of the fight against the Bolsheviks.

Vasily Vitalievich Shulgin- an amazing person. It is difficult to say what was more in him: the prudence of a politician or the adventurism of Ostap Bender. We can say for sure that his life was like an adventure novel, which sometimes turned into a thriller.

Dmitry Ivanovich Pikhno, Shulgin's stepfather. Source: Public Domain

“I became an anti-Semite in my last year at university”

He was born in Kyiv on January 13, 1878. His father was a historian Vitaly Shulgin, who died when his son was not even a year old. Then Vasya’s mother passed away: his stepfather took custody of the boy, economist Dmitry Pikhno.

Shulgin studied mediocrely, was a C student, but after high school he entered the Kiev Imperial University of St. Vladimir to study law at the Faculty of Law. His stepfather's connections and noble origin helped.

Pikhno was a convinced monarchist and nationalist and passed on similar beliefs to his stepson. In student circles, on the contrary, revolutionary sentiments reigned: Shulgin was a “black sheep” at the university.

“I became an anti-Semite in my last year at university. And on the same day, and for the same reasons, I became a “rightist,” a “conservative,” a “nationalist,” a “white,” well, in a word, what I am now,” Shulgin said about himself in adulthood.

By the beginning of the first Russian revolution, Shulgin was an accomplished family man, had his own business, and in 1905 he began actively publishing his articles in the Kievlyanin newspaper, which was once headed by his father, and at that time by his stepfather Dmitry Pikhno.

Best speaker of the State Duma

Shulgin joined the organization "Union of the Russian People", and then joined the "Russian People's Union named after Michael the Archangel", which was headed by the most famous Black Hundred member Vladimir Purishkevich.

However, Purishkevich’s radicalism was still not close to him. Having been elected to the State Duma, Shulgin moved to more moderate positions. Being initially an opponent of parliamentarism, over time he not only began to consider popular representation necessary, but he himself became one of the most prominent speakers in the State Duma.

Shulgin’s atypicality as a Black Hundred man became apparent during the scandalous Beilis case, which involved accusations of Jews ritual murders Christian children. Shulgin, from the pages of Kievlyanin, directly accused the authorities of fabricating the case, which is why he almost ended up in prison.

With the outbreak of the First World War, he volunteered to go to the front, was seriously wounded near Przemysl, and then headed the front-line feeding and dressing station. From the front to Petrograd he went to State Duma meetings.

Witness of renunciation

Having met February 1917 in the strange role of a liberal monarchist, dissatisfied with the policies of Nicholas II, Shulgin was a categorical opponent of the revolution. Even more: according to Shulgin, “the revolution makes you want to take up machine guns.”

But in the very first days of the unrest in Petrograd, he begins to act as if guided by the principle “if you want to prevent it, lead it.” For example, Shulgin, with his fiery speeches, ensured the transition of the garrison of the Peter and Paul Fortress to the side of the revolutionaries.

He was included in the Temporary Committee of the State Duma, which, in essence, was the headquarters of the February Revolution. In this capacity, together with Alexander Guchkov he was sent to Pskov, where he accepted the act of abdication from the hands of Nicholas II. The monarchists could not forgive Shulgin for this until the end of her life.

Shulgin with an employee during his visit to Nicholas II for abdication. Pskov, March 1917 Source: Public Domain

The enemy of Ukrainian nationalism

The revolutionary wave, however, soon pushed him to the periphery, and he left for Kyiv, where even greater chaos was happening. This is where the factor comes into play Ukrainian nationalists, which Shulgin tried to fight with all his might, protesting against plans for “Ukrainization.”

Shulgin was involved in the attempted mutiny General Kornilov and was even arrested after his failure, but he was quickly released.

After the October Revolution, Shulgin went to Novocherkassk, where the formation of the first White Guard units was underway. But General Alekseev, who was dealing with this issue, asked Shulgin to return to Kyiv and start publishing the newspaper again, considering him more useful as a propagandist.

Power in Kyiv passed from hand to hand. Shulgin, arrested by the Bolsheviks, was released by them during the retreat. Apparently, knowing his views, the Reds decided not to leave Shulgin to be dealt with by the Ukrainian nationalists.

When Kyiv was occupied by German troops in February 1918, Shulgin closed his newspaper, writing in last issue: “Since we didn’t invite the Germans, we don’t want to enjoy the benefits of relative peace and some political freedom that the Germans brought us. We have no right to this... We are your enemies. We may be your prisoners of war, but we will not be your friends as long as the war continues.”

Brief triumph followed by flight

Agents of France and Great Britain appreciated Shulgin’s impulse and offered him cooperation. Thanks to their help, Shulgin began to create an extensive intelligence network, called “ABC,” which made it possible to collect information, including in the territory occupied by the Bolsheviks.

He made enemies very quickly. The monarchists could not forgive him for his trip to Pskov; for the Bolsheviks he was an ideological opponent, and Hetman Skoropadsky and completely declared him a “personal enemy.”

Having got out of Kyiv, he reached Yekaterinodar, occupied by whites, where he published the newspaper “Russia”. Then in Odessa he acted as a representative of the Volunteer Army, from where he was forced to leave after a quarrel with the French occupation authorities.

In the summer of 1919, the Whites took Kyiv: Shulgin returned home in triumph, resuming the production of his “Kievlyanin”. The triumph was, however, short-lived: in December 1919, the Red Army entered the city and Shulgin barely managed to get out at the last moment.

He moved to Odessa, where he tried to rally the anti-Bolshevik forces around himself, but as good as Shulgin was as an orator, he was just as unimportant an organizer. The underground organization he created after the occupation of Odessa by the Reds was discovered, and the former State Duma deputy had to flee again.

Portrait of V.V. Shulgin in exile, 1934 Source: Public Domain

In the web of the "Trust"

After the final defeat of the whites in the Civil War, he moved to Constantinople. Shulgin lost many loved ones, including his two eldest sons. One of them died, and he knew nothing about the fate of the second for several decades. Only in the sixties did Shulgin learn that Benjamin, whose family name was Lyalya, died in the USSR in a psychiatric hospital in the mid-twenties.

In the first years of emigration, Shulgin wrote many journalistic works, advocated for the continuation of the struggle, and collaborated with the Russian All-Military Union (ROVS). On his instructions, he illegally went to the USSR, where an organization was operating that was preparing an anti-Bolshevik coup. After his return, Shulgin wrote the book “Three Capitals,” in which he described the USSR during the heyday of the NEP.

The book turned out to be too complimentary to Soviet reality, which many in the emigration did not like. And then a scandal broke out: it turned out that the underground organization in the USSR was part of an operation of the Soviet special services under code name Shulgin spent the “Trust” and the entire trip under the close tutelage of GPU employees.

Shulgin was shocked: until the end of his life he did not believe that he had fallen for the bait of the security officers. Nevertheless, he withdrew from active work in exile after the “Trust” scandal.

25 years instead of the gallows

In the thirties, Vasily Vitalievich looked into the abyss: he was among those Russian emigrants who welcomed the arrival Hitler to power and initially saw it as a way to liberate Russia from the Bolsheviks. Fortunately for himself, Shulgin managed to recoil in time, otherwise his story most likely would have ended the same way as the story generals Krasnov And Skin: Having sworn allegiance to Hitler, they were eventually hanged in Lefortovo prison in 1947.

Shulgin, who lived in Yugoslavia, after its liberation from the German occupation, was detained and sent to Moscow. An active member of the White Guard organization “Russian All-Military Union” was sentenced to 25 years in prison in the summer of 1947.

He later recalled that, of course, he expected punishment, but not so severe, calculating that, taking into account his age and the fact that a lot of time had passed since his active work, he would be given three years.

Shulgin sat in the Vladimir Central together with German and Japanese generals, the disgraced Bolsheviks and other notable persons.

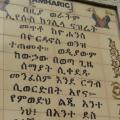

Photo of Shulgin from the materials of the investigative case.